“If people could see into my heart I should almost feel ashamed.”

It’s hardly surprising that humanity’s most beautiful minds — the creative visionaries who bequeath us with the finest works of art, music, and literature — should also be the ones who author the most bewitching

love letters, that highest form of what Virginia Woolf called

“the humane art.” One particularly heartwarming specimen of the genre comes from

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (January 27, 1756–December 5, 1791) — doubly so for the unusual start of the romance that would become the love of his life.

In late 1777, Mozart fell in love with Aloysia Weber — one of four daughters in a highly musical family. Despite the

early cultivation of his talent, he was only just beginning to find self-actualization; she, on the other hand, was already a highly successful singer. (A century later, another great composer — Tchaikovsky — would

tussle with the same challenge.) Despite her initial interest, Aloysia ultimately rejected his advances.

Over the next few years, Mozart established himself not only as the finest keyboard player in Vienna, but also as a promising young composer. When the father of the family died in 1782, the Webers began renting their house to lodgers to make ends meet. Young Mozart moved in, and soon fell in love with Constanze — the third Weber daughter.

On August 4, 1782, the two were married and remained together, very much in love, until Mozart’s death nine years later.

Shortly before his sudden death, in a letter from September of 1790 found in

Love Letters of Great Men (

public library) — a collection of romantic correspondence featuring Lord Byron, F. Scott Fitzgerald, James Joyce, Voltaire, Leo Tolstoy, and dozens more lovers of letters — Mozart writes to Constanze from Frankfurt, where he had gone seeking gainful employment to remedy the family’s financial downturn:

Dearest little Wife of my heart!

If only I had a letter from you, everything would be all right…

Dearest, I have no doubt that I shall get something going here, but it won’t be easy as you and some of our friends think. — It is true, I am known and respected here; but, well — No — let us just see what happens. — In any case, I do prefer to play it safe, that why I would like to conclude this deal with H… because I would get some money into my possession without having to pay any out; all I would have to do then is work, and I shall be only too happy to do that for my little wife.

After a getting a few more practical matters out of the way, Mozart fully surrenders to the poetical:

I get all excited like a child when I think about being with you again — If people could see into my heart I should almost feel ashamed. Everything is cold to me — ice-cold. — If you were here with me, maybe I would find the courtesies people are showing me more enjoyable, — but as it is, it’s all so empty — adieu — my dear — I am Forever

your Mozart who loves you

with his entire soul.

PS. — while I was writing the last page, tear after tear fell on the paper. But I must cheer up — catch — An astonishing number of kisses are flying about — The deuce! — I see a whole crowd of them. Ha! Ha!… I have just caught three — They are delicious… I kiss you millions of times.

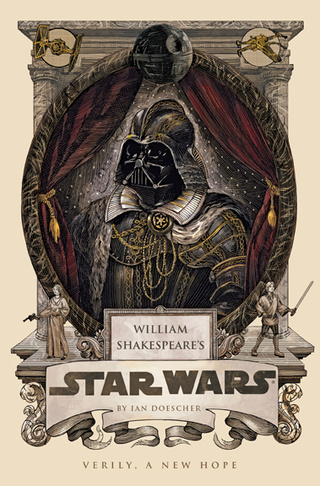

Though William Shakespeare regularly dominates surveys of the greatest literature of all time, he remains a surprisingly controversial figure of literary history — while some believe The Bard profoundly changed modern life, others question whether he wrote anything at all. Doubts of authorship aside, one thing Shakespeare most certainly didn’t write is the cult-classic Star Wars — but he, as Ian Doescher brilliantly imagines, could have: Behold William Shakespeare’s Star Wars (public library), a masterwork of literary parody on par with the household tips of famous writers andEdgar Allan Poe as an Amazon reviewer.

Though William Shakespeare regularly dominates surveys of the greatest literature of all time, he remains a surprisingly controversial figure of literary history — while some believe The Bard profoundly changed modern life, others question whether he wrote anything at all. Doubts of authorship aside, one thing Shakespeare most certainly didn’t write is the cult-classic Star Wars — but he, as Ian Doescher brilliantly imagines, could have: Behold William Shakespeare’s Star Wars (public library), a masterwork of literary parody on par with the household tips of famous writers andEdgar Allan Poe as an Amazon reviewer.