How working for the wrong motives poisons our creativity and warps our ideas of success and failure.

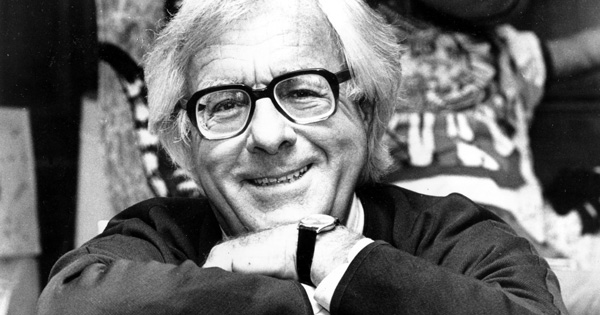

“A master in the art of living draws no sharp distinction between his work and his play,” the French writer Chateaubriand is credited with saying. “He simply pursues his vision of excellence through whatever he is doing, and leaves others to determine whether he is working or playing. To himself, he always appears to be doing both.” Few contemporary creators embody this more wholeheartedly than Ray Bradbury — belovedwriter, a man of admirable routine, tirelessadvocate of space exploration and public libraries, passionate proponent of doing what you love and writing with joy, champion ofintuition over the intellect.

“A master in the art of living draws no sharp distinction between his work and his play,” the French writer Chateaubriand is credited with saying. “He simply pursues his vision of excellence through whatever he is doing, and leaves others to determine whether he is working or playing. To himself, he always appears to be doing both.” Few contemporary creators embody this more wholeheartedly than Ray Bradbury — belovedwriter, a man of admirable routine, tirelessadvocate of space exploration and public libraries, passionate proponent of doing what you love and writing with joy, champion ofintuition over the intellect.

From Zen in the Art of Writing (public library) — one of my favorite books on writing, which also gave us Bradbury on how list-making can boost your creativity — comes some timeless wisdom on work, motivation, and creating from a place of love.

A century after Swami Vivekananda’s poignant meditation on the secret of meaningful work, Bradbury considers why we hate work, as a culture and as individuals:

Why is it that in a society with a Puritan heritage we have such completely ambivalent feelings about Work? We feel guilty, do we not, if not busy? But we feel somewhat soiled, on the other hand, if we sweat overmuch?I can only suggest that we often indulge in made work, in false business, to keep from being bored. Or worse still we conceive the idea of working for money. The money becomes the object, the target, the end-all and be-all. Thus work, being important only as a means to that end, degenerates into boredom. Can we wonder then that we hate it so?[...]Nothing could be further from true creativity.

Like Tolstoy, who some decades earlier admonished against writing for money and fame, and like Michael Lewis, who some decades later advised aspiring writers to find any motive but money, Bradbury argues that writing for either commercial rewards or critical acclaim is “a form of lying.”

This warping of motive can also deform our definitions of success and failure. Echoing Leonard Cohen’s wisdom on why you should never quit before you know what it is you’re quitting, Bradbury writes:

We should not look down on work nor look down on [our early works] as failures. To fail is to give up. But you are in the midst of a moving process. Nothing fails then. All goes on. Work is done. If good, you learn from it. If bad, you learn even more. Work done and behind you is a lesson to be studied. There is no failure unless one stops. Not to work is to cease, tighten up, become nervous and therefore destructive of the creative process.

(Nearly twenty years later, Oprah would mirror this closely and counsel the graduating class at Harvard that “there is no such thing as failure — failure is just life trying to move us in another direction.”)

A lifelong advocate of doing what you love, Bradbury ends with a beautiful disclaimer for the cynical:

Now, have I sounded like a cultist of some sort? A yogi feeding on kumquats, grapenuts and almonds here beneath the banyan tree? Let me assure you I speak of all these things only because they have worked for me for fifty years. And I think they might work for you. The true test is in the doing.Be pragmatic, then. If you’re not happy with the way your writing has gone, you might give my method a try.If you do, I think you might easily find a new definition for Work.And the word is LOVE.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire